home | contact | sound samples | discography | calendar | reviews and testimonials | photos and press materials | site map | mailing list sign-up |

||

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

Essay by Michael Arnowitt, December 2020

Here is the fifth of a series of mini-essays I’m writing on music. This one explores the beginning of Beethoven’s Sonata 28 in A major, opus 101 and Debussy’s “La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune” from his Preludes book 2, number 7.

A good thing for the performing musician to bear in mind is that there is a huge difference between what you and the audience knows about the piece of music you are going to play. You know the piece in great detail because you have practiced the music for hours at home, but nearly all of the audience is starting from ground zero and is absorbing the sounds coming at them in real time. This means such basic things you know full well as what is the key (the home tonality of the piece) and what is the meter (how many beats there are per measure) is not going to be obvious to the audience member as you play the piece, many hearing these sounds for the first time. You have to establish for the listener’s ear these foundational elements of the harmony and rhythm which are self-evident to you looking at the music in the book but are not going to be as clear to the audience. Because of this, the first few measures of a piece are important to getting the listener acclimated. This is parallel to a news reporter launching into their story without telling you what city they are reporting from, or a journalist beginning an interview without telling you who they are interviewing.

I once went to a concert where a friend of mine, now no longer alive, was performing Bach’s Goldberg Variations. The melody begins with two quarter notes and then an ornamented dotted rhythm. On this third beat of the first measure of the entire piece, the pianist lavished a huge amount of rubato, that is, a romantic lingering in time, over the dotted rhythm and ornament. To me, this was a really strange decision because it was only the first measure and the listener is just settling in and does not even know yet that the piece is in three beats per measure.

Good composers, though, sometimes seem to play around with this phenomenon that at the beginning of a piece the listener lacks the context to know where they are musically. I recently attended an online orchestra concert conducted by my friend Piotr Gajewski and he pointed out in his pre-concert talk the listener confusion that results from the first two chords of Beethovenís first symphony, which begins with a C7 chord resolving to an F major chord. Normally, this would suggest you are in F major, but Beethoven follows up with a series of chords that eventually clue you in that we were actually in C major all along. As you are listening to these opening chords, the music is ambiguous and you donít really know what key you are in for a few measures. As I mentioned in a previous post about the beginning of Beethoven’s Sonata 30 opus 109, I’m beginning to see how often ambiguity in music creates beauty.

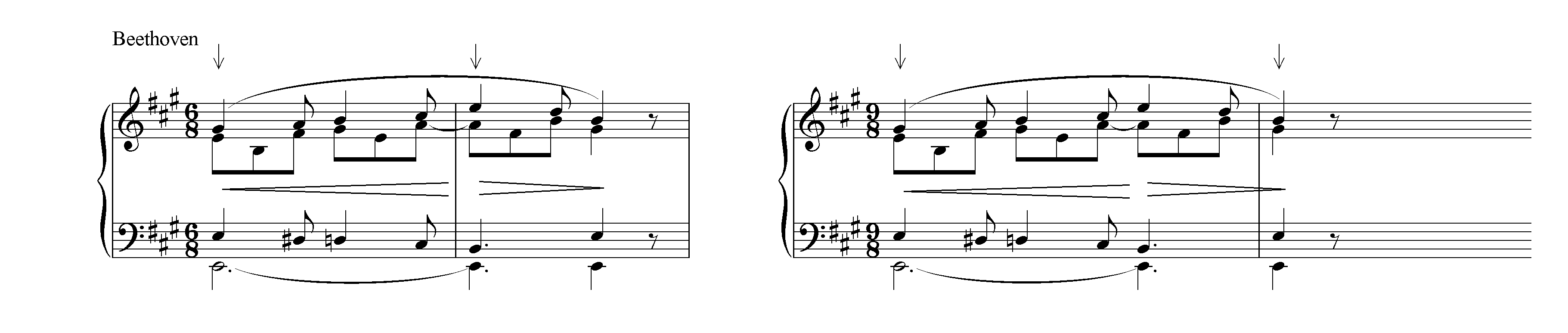

Now let’s take a look at the opening of one of my favorite Beethoven piano sonatas, number 28 opus 101 in A major. Pictured below on the far left are the opening two measures of the piece. This sonata was written near the end of Beethoven’s life and the writing here reminds me of the composer’s great final string quartets. In the lower staff played by my left hand, we can imagine the stems down notes as a cello line, the higher stems up notes a deep low viola, and on the upper staff played by my right hand the beautifully meandering stems down line played by a second violin and at the top of the texture the stems up notes of a first violin melody.

At the left of the first line Iíve written the notes as in the printed music, in a time signature of 6/8, which means there are six eighth-note beats per measure. In 6/8 meter there are two major beats per measure, on the 1st and 4th eighths of the six. Looked at this way, the music fills two whole measures, and it makes sense from the point of view of the first violin line rising to its peak perfectly at the beginning of the second measure and the viola line, in contrary motion, descending to its bottom-most note also exactly where the second measure might begin if 6/8 were the time signature. Another data point is that Beethoven asks for a crescendo during the first measure and a decrescendo during the second measure, so this swell is also consistent with hearing this music as suggestive of a 6/8 meter.

However, the listener could also easily sense this music as if it had been written in a meter of 9/8, which I’ve written out for contrast in the two measures at the right of the first line. A 9/8 measure has three major beats, not two, with strong subdivisions on the 1st, 4th, and 7th of the 9 eighth-notes of a measure. Why would your blank slate listener with no prior knowledge perceive the music in my 9/8 alternate universe? Well, you have the first violin melodyís rhythm which has three quarter-plus-eighth pairs in a row, so that pattern sounds like one extended group filling a long 9 eighth-note measure. You have the cello holding a long note for all of these nine beats. And most importantly, all four layers of the texture come together and play simultaneously an E major chord at the end of the phrase. So it would be entirely natural to hear the last chord as the beginning of the second measure rather than, if the music was in 6/8, halfway through the second measure (as is the case in the first version on the left). I have placed above the music downward arrows to indicate where the strong beats align in the two possible interpretations. The notes and rhythms in the two versions are exactly the same: the only difference is the structure of the meter, which influences how a pianist would play and how a listener would hear the phrase.

In reality, the music is ambiguous. You can hear it one way, or the other way, or possibly both at the same time. The musicís meter ambiguity confusion is pleasant and contributes to the general ethereal and suspended feeling which is the predominant mood you hear in the music Beethoven wrote to follow this first phrase.

In this opening part of the sonata Beethoven moves beautifully from moments like this string quartet style music to moments where the texture is more pianistic or even orchestral, the different types of scenes entering and exiting gracefully like film dissolves.

Currently, I’m learning a Debussy prelude, “La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune” from his Preludes book 2, number 7. The title is a quotation from a poem of Baudelaire. As it turns out, my favorite prelude from Debussyís book 1 collection is also titled with a quotation from a Baudelaire poem, “Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l'air du soir” which I am relearning. Debussy cleverly placed these “titles” under the final page of each prelude in the bottom right corner after a three dots ellipsis, presumably to downplay their importance and suggest the pianist not take these titles too literally.

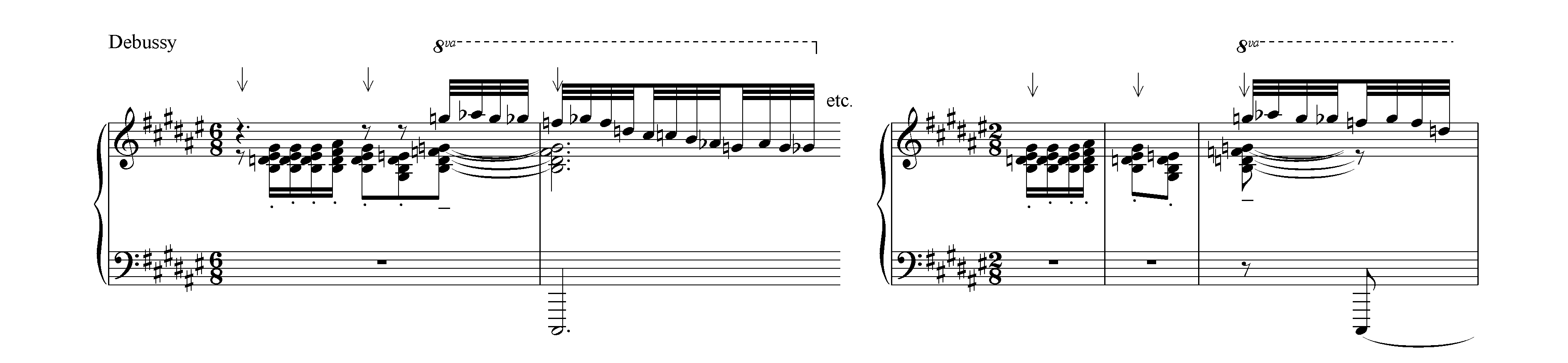

On the left side of the image below you can see the opening of the prelude as Debussy composed it, again, like the Beethoven, in a time signature of 6/8. The 6 eighth-notes are divided into two main groups, beginning at the 1st and 4th eighth-notes of the measure, indicated here by downward arrows. In this version Debussy published, the first chord begins not on the first eighth of the measure, but on the second eighth after an initial rest is marked. However, out there in audience-land, you can’t hear this silent rest, so it would be quite possible for a listener to understand this first sound of the piece as aligned with a strong beat of the measure, rather than as Debussy wrote here an offbeat reaction sounding only after the strong first beat of the measure has already passed. My alternate universe thought experiment would be the music written to the right, in a meter of 2/8. Again, the notes and rhythms in the two versions are identical, but the two different meters change which notes align with the strong beats, which I’ve marked with the downward arrows.

As in the Beethoven example, some aspects of the music suggest one interpretation of what the meter is, some the other. The first version in 6/8 with the initial entrance occurring offset from the first beat makes the moment where the chords in the middle of the pianoís switch from sixteenth notes to eighth notes align with a strong beat on the 4th eighth of the 6. It also makes the super low C# bass note entrance line up with the beginning of the second measure. However, in the second version in 2/8 with the first chord conceived of right on the beat, the super high 32nd note entrance and its supporting chord underneath it in the middle of the piano (which Debussy marks with a stress indication) are now nicely aligned with a strong beat. Against that, the low note entrance is now no longer on a strong beat, but an offbeat. These conflicting messages as to where are the strong and weak beats help give the music its flexible, elastic quality.

I realize these listening sensations go on inside us only unconsciously, , yet I find all these ways composers create music that can be heard in multiple ways totally fascinating. The more I think about it, the more Iím convinced that ambiguity is what gives music beauty. Some of my upcoming mini-essays will further explore this theme looking at diverse music, from Jobim’s The Girl from Ipanema, the beginning of Tchaikovsky’s first piano concerto, and a Mozart symphony, to some famous Shakespeare speeches from Hamlet and Julius Caesar.