home | contact | sound samples | discography | calendar | reviews and testimonials | photos and press materials | site map | mailing list sign-up |

||

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

Essay by Michael Arnowitt, December 2020

An idea that’s been gelling in my mind a lot the past few weeks is that ambiguity in music is beautiful and is what gives music its richness.

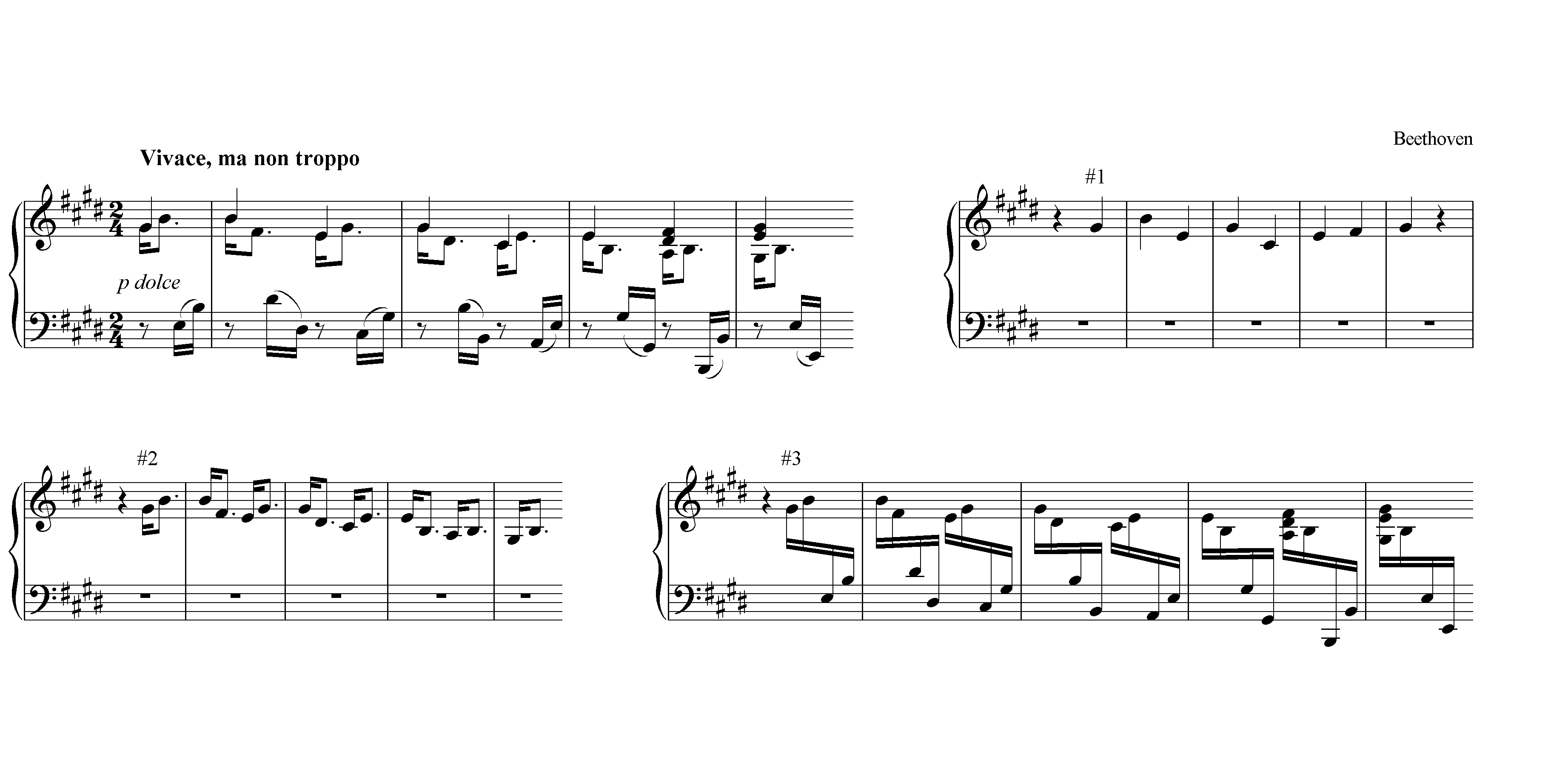

This thought has been cropping up for me in a number of diverse musical contexts recently, from Debussy to Mozart to jazz, but here’s one fantastic example for today: the Opening four measures of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata 30 in E major, opus 109, pictured below.

At the beginning of the first line you can see the original music Beethoven wrote for the opening phrase of the sonata. The melody, played by my right hand in the top staff, is composed of little two-note groups which alternate going up and down in a pattern that gradually moves down the piano. Underneath the right handís melody, the left hand has some accompanying music which also contains two-note groups, also meanders gradually downward on the piano, but has slightly wider leaps between the two notes of each individual pair. Sounds pretty simple: melody and accompaniment. However, Beethoven does a few subtle things that produce music that can be heard three different ways, which I’ve illustrated as #1, #2, and #3.

At the beginning of the excerpt on the upper left, the melody of two-note groups is indicated by Beethoven by the notes with downward stems. To make this melody easier to see, Iíve separated out these notes by themselves where Iíve marked #2, at the beginning of the second line. Each of these two-note units is a Scottish “reverse dotted rhythm” where the first note of each pair takes up 1/4 of the beat and the second note takes up the remaining 3/4 of the beat. Beethoven creates an interesting layer to the texture here by asking the pianist to hold the first note of each group of two notes throughout the entirety of the beat. This is indicated by the upward stems on the first of each group of two notes. I’ve separated these notes out at #1 at the end of the first line.

In this way Beethoven has formed a second melody of even quarter notes that flows along simultaneously with the Scottish reverse dotted rhythm melody. It is a beautiful ambiguity, as your ear can focus either on the sustained melody notes of #1 or the jaunty melody of #2. In real life I suspect oneís attention flips back and forth between the two ways of listening to these notes, or, perhaps, can possibly hear both layers at the same time.

But Beethoven’s not done yet. Because the left hand accompaniment always plays inbetween the right hand’s two-note groups, you only hear one note played in either hand at any one time. Since the hands never play together, this means the ear can hear this opening phrase a third way, presented at #3 at the end of the second line. Here a composite line, like weaving, is created where two notes higher up in the right hand and two notes answering lower down in the left hand combine to make a unified running line of groups of four sixteenth notes in a steady pattern. In this way Beethovenís interlocking placement of notes blurs and makes ambiguous what is melody and what is accompaniment.

In reality, because in the right hand’s melody I’m supposed to carefully hold the second note of each pair to the end of the beat, if you listen closely enough the four notes of each group of sixteenths are not weighted equally. The music is full of ambiguity, different ways that tantalize the ear as possible understandings of this multi-faceted music.

Other pieces I’ve been listening to recently that have brought to mind how composers create beauty through ambiguity are the beginnings of Beethoven’s Sonata no. 28 in A major, opus 101, Debussy’s Prelude no. 7 from book 2 “La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune”, the beginning of Mozart’s Haffner Symphony, and the middle section of Jobim’s The Girl from Ipanema - I plan to write about all these pieces in future posts.

Music’s ambiguity is its strength; the best composers seem to like to create music that is not cut and dried but can be heard in multiple ways. Ambiguity in music is what makes it beautiful.