home | contact | sound samples | discography | calendar | reviews and testimonials | photos and press materials | site map | mailing list sign-up |

||

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

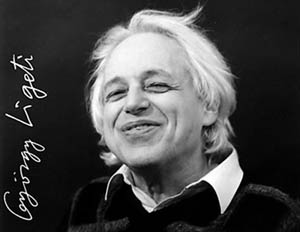

Ligeti And His InfluencesMusic to wow both the mind and the body

Program --

Description of program - long version Ligeti and his Influences Musical pioneer György Ligeti, who died in June at the age of 83, was one of the world’s greatest composers. Over the past twenty years, he turned his hand to the writing of solo piano music, producing a remarkable series of piano études universally acknowledged as a worthy successor to the famous étude sets of Chopin and Debussy. Ligeti, a Holocaust survivor of forced labor camps for Jews in his native Hungary, eventually emigrated to western Europe in the 1950’s where he has remained to the present day, primarily living in Vienna. He is best known in America for his evocative, atmospheric music in the hit film “2001: A Space Odyssey.” In 1985 he composed the Études for piano, Book 1, soon followed by Book 2 which contained pieces written from 1988 to 1994. “Étude” literally means a study of significant technical difficulty, and while the history of music is littered with empty display pieces, great composers of the past have long recognized that the virtuosity customary in this type of music can be successfully married to the higher goal of creating art that will emotionally move the listener rather than merely impress with flying fingers. Ligeti’s études are viscerally exciting pieces, enormously stimulating to both the body and the mind, possessing at the highest artistic level music of colorful harmonies, rhythmic vitality, and extraordinary piano textures never before imagined. His books of études were promptly deemed to be among the best piano pieces of the last twenty years. More recently, they have been called the best piano pieces of the last 50 years. As our perspective has grown, Michael Arnowitt now believes Ligeti’s études will soon be recognized as the best piano pieces of the entire twentieth century. We know the composing of these études continued to interest Ligeti, as from 1995 until his death this past summer he had been working on a third book of piano études, the first four of which were published in 2005. Michael Arnowitt has chosen to present Ligeti’s études in concert with a bit of a twist: his selection of études will comprise the second half of the program, led up to with a first half of pieces of music by a variety of other composers who influenced Ligeti. For the 1996 premiere recording of his études, Ligeti wrote an unusually revealing set of liner notes, and from these clues Michael Arnowitt researched and selected particular compositions he regards as foreshadowing the most interesting aspects of Ligeti’s pianistic style. These “blasts from the past” make many illuminating connections to Ligeti’s wonderful études of our own time. By listening first to the earlier piano music that inspired Ligeti’s creations, and only then to the études themselves, the audience gains a far greater understanding of what makes Ligeti’s music tick. Ligeti said “for a piece to be well-suited for the piano, tactile concepts are almost as important as acoustic ones.” In composing these études, Ligeti experienced a feedback loop between his imagination - the ideas he hears with his inner ear - and the “anatomical reality of my hands and the configuration of the piano keyboard.” As he tried out different concepts at an actual piano, these initial ideas would be transformed. “I have to feel them out with my hand,” he said. According to Ligeti, he “called for support” on the “four great composers who thought pianistically: Scarlatti, Chopin, Schumann, and Debussy.” The program begins with a short set of Scarlatti’s remarkable miniature keyboard sonatas. Although written 250 years before Ligeti’s piano music, Scarlatti’s music offers the same sort of brilliant colors and exciting whilrwind washes of sound utilizing every nook and cranny of the keyboard, from extreme high to extreme low. Like Scarlatti, Chopin’s music plays on our appreciation not only of our sense of sound but of our sense of touch. Ligeti wrote, “a Chopinesque melodic twist or accompaniment figure is not just heard; it is also felt as a tactile shape.” Indeed, the beautifully long, curved, almost vine-like lines Chopin pioneered in piano music (heard on this program in his Nocturne op. 55 no. 2) is also present in many of Ligeti’s études (such as no. 2, Open Strings). Another Chopin piece on this program, the “Aeolian Harp” étude op. 25 no. 1, is one of the earliest “minimalist” pieces to be written after J.S. Bach’s landmark Prelude no. 1 in C major from the Well-Tempered Clavier. In minimalist music, a pattern is repeated in a continuous flow with only one or two notes of the pattern changed upon repetitions. Ligeti noted his strong interest in the notion of a super-fast “elementary pulse” found in sub-Saharan African percussion ensemble music, a traditional type of music which also was cited as an influence by the American minimalist composers in the 1970’s. While the repetitions in Bach’s prelude have a sturdy, deliberate, and architectural character, the moments in Ligeti’s études which have a minimalist flavor (such as no. 10, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice) are clearly closer to the shimmering, coloristic atmosphere that Chopin created in his magical “Aeolian Harp” étude. Unlike Bach’s prelude or modern era examples by Steve Reich and Philip Glass, Ligeti spices up the regular pulses by tossing in irregular accents on certain notes in one hand or the other: the listener’s ears begin to “connect the dots,” hearing new lines formed from the sequence of these accented notes; these new lines sometimes feel as though they are moving at a different speed from the underlying beat. The most obvious precedent to Ligeti’s piano études is Claude Debussy’s two books of études, composed in the early twentieth century. Although Chopin’s collection of études is far more famous, these pieces by Debussy, composed near the end of his life, show a greater kinship with the études of Ligeti. Michael Arnowitt has selected two of Debussy’s études for this program: the sixth, “pour les huit doigts” is filled with cascades of quicksilver ascending and descending lines at top speed that create a tingling sensation similar to many virtuoso moments in the Ligeti études. Debussy’s invention of the ethereal whole-tone scale is presented in a novel way in Ligeti’s seventh étude, Galamb borong: the right hand plays exclusively notes of a whole-tone scale based on a B-natural, while the left hand only plays notes drawn from its complementary whole-tone scale based on B-flat. The two hands playing together produce a beautiful effect of out-of-tuneness, which Ligeti may have intended as a piano simulation of the sound of Balinese gamelan instruments. Debussy’s masterful creations of new piano textures, combining in a most sensitive way light brushstrokes of bell-like sounds in many different parts of the piano, was a model for Ligeti’s own texture creations in études such as no. 11, En suspens. Perhaps Debussy’s greatest contribution to music was freeing it from the rhetoric of the great German-Austrian composers of the prior 150 years, whose phrases build upon each other in logical structures derived from classic Greek oratory. Although these parallels with our experiences as humans with the spoken word were very powerful, Debussy ventured in a different direction, making music that evolves and flows in a much more flexible way so reminiscent of the movement of water in the natural world. Ligeti appreciated this fluidity and spoke of how many of his études begin with a simple core idea and then “behave like growing organisms.” Robert Schumann had an uncanny knack for creating new sounds for the piano; the two hands of the pianist regularly create in his music three or even four part textures. His Novellette op. 21 no. 1 has an astonishing episode in the middle where descending scales continually overlap each other in a wave-like manner. Some of Ligeti’s best music in these études evokes a similar sensation of overlapping waves, with the additional wrinkle that the waves continually come from the horizon to the shore from different directions and constantly varying time intervals, creating stimulating interference patterns. Another piece by Schumann on the program, his youthful Toccata op. 7, is a spirited showcase of rhythmic games and humor, both strong elements of Ligeti’s style. Ligeti stated on several occasions his great admiration for the music of Conlon Nancarrow, the American-born Mexican composer whose primary lifetime work was a series of over 50 studies for player piano. These fantastic and unique pieces of music were written in isolation at Nancarrow’s residence on the outskirts of Mexico City between the late 1940’s and the early 1990’s. News of the player piano studies spread quickly by word of mouth from fascinated musicians who had made the pilgrimage to the composer’s studio in Mexico, and Nancarrow became a cult figure despite the fact that it took 20 to 30 years before these pieces were recorded and published. Nancarrow’s music focuses on rhythmic adventures where different voices in a texture proceed simultaneously at different speeds. Near the end of his life, Nancarrow wrote a number of compositions for live performers. On this program, his Canon for Ursula no. 2 starts with the left hand alone, playing a humorous melange of glissandi swoops, tango accompaniments, and a fast boogie-woogie figuration. The right hand later enters, playing approximately the same music at a faster general speed: the tortoise and the hare meet exactly on the last measure of the piece, at the figurative finish line. Although the basic concept is mathematical, the realization of it is anything but dry, and many of the funny gestures in the piece are rooted in experiences from Nancarrow’s early years, where in addition to his studies as a classical composer he worked as a jazz trumpeter. Ligeti expanded on some of Nancarrow’s ideas in his sixth étude, Autumne à Varsovie (Autumn in Warsaw), where not only does the pianist play in up to four different speeds at the same time, but an individual part of the texture can change speed over time from 3 to 4 to 5 to 7, speeding up gradually or slowing down. All these individual lines are played over an “underlying gridwork” of fast, regular pulsations; as one of the parts that changes speed criss-crosses this background of pulsating notes, fascinating patterns are created along the way. Ligeti’s influences go beyond past and present classical composers and the traditional musics of Africa and Indonesia: he has also revealed his interest in American jazz, singling out for special praise the pianists Thelonius Monk and Bill Evans. Monk’s eccentric, angular style of improvisation can be heard distilled in the opening melody of his tune Epistrophy. Ligeti’s étude no. 4, Fanfares, has passages where first the right hand, and then the left, play Monk-like short, zany improvisatory fragments while the other hand accompanies with a series of eight quirky running notes that repeat in a short loop much in the nature of a “vamp” figure in jazz. The jazz pianist Bill Evans’ luminous, dense chords, heard here in his version of “Young and Foolish,” is mirrored in Ligeti’s fifth étude, Arc-en-ciel (Rainbow). The chords developed by Evans have been dubbed “rootless,” as they frequently omit the fundamental root note of the chord, thereby creating a lighter floating, suspended feeling. A jazzy rhythmic “swing” feel is called for by Ligeti in the performance notes to his eighth étude, Fém, a Hungarian word indicating a bright metal. Ligeti’s influences run even beyond all these different composers and types of music to his non-musical interests such as topology, the fractal geometry of Benoit Mandelbrot and the writings of Heinz-Otto Peitgen on chaos theory, the unusual still-lifes of Paul Cézanne, the sculptures of Constantin Brancusi of Romania, and the fantastical perspective of M.C. Escher’s artwork. Ligeti’s études are full of sensual music exhilarating to both pianist and audience. It is joyful music, but a different type of joy than what we experience in the great romantic masterpieces of history. His landscapes and washes of water-like sound take the impressionism and beauty of Debussy into another dimension informed by recent scientific inquiry and Ligeti’s own personal visions. This is music that beguiles and touches our sense of wonder and imagination. Shorter description Ligeti and his InfluencesMusic to wow the mind and the body Musical pioneer György Ligeti, who died in June at the age of 83, was one of the world’s greatest composers. Over the past twenty years, he wrote a remarkable series of three books of piano études universally acknowledged as a worthy successor to the famous étude sets of Chopin and Debussy. These viscerally exciting pieces, enormously stimulating to both body and mind, possess at the highest artistic level music of colorful harmonies, rhythmic vitality, and extraordinary piano textures never before imagined. Already frequently cited as the best piano pieces composed since World War II, Arnowitt believes these études will soon be recognized as the finest piano pieces of the entire twentieth century. Ligeti, a Holocaust survivor of forced labor camps for Jews in his native Hungary, eventually emigrated to Vienna. He is best known in America for his evocative, atmospheric music in the hit film “2001: A Space Odyssey.” For this concert, Michael Arnowitt has made a special selection of Ligeti études to form the second half of the program. These pieces will be led up to by a first half of works by other composers who influenced Ligeti. According to Ligeti, the “four great composers who thought pianistically” were Scarlatti, Chopin, Schumann, and Debussy. Included on this program are a set of sparkling Scarlatti sonatas, a Chopin nocturne with long, vine-like lines and his shimmering, quasi-minimalist “Aeolian Harp” étude, a Schumann Novellette and Toccata, and two of Debussy’s best études, including the famous “Pour les arpèges composés.” The program continues with music by two jazz pianists Ligeti cited as favorites, Thelonious Monk and Bill Evans, and a lively piece by the mid-20th century composer Conlon Nancarrow, whose experiments with rhythm Ligeti greatly admired. Together, these pieces foreshadow many aspects of Ligeti’s pianistic style, illuminating Ligeti’s many interests, such as fractal geometric shapes, interference patterns created when waves approach us from different directions, textures with simultaneous, multiple speeds overlaid upon a gridwork of African pulse music, and the most delicate use of every nook and cranny of the keyboard. Ligeti’s landscapes take impressionism into another dimension. Back to Home Page |