home | contact | sound samples | discography | calendar | reviews and testimonials | photos and press materials | site map | mailing list sign-up |

||

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

Essay by Michael Arnowitt, March 2021

What makes a memorable melody is a good question. In an essay by Leonard Bernstein I read growing up in his anthology The Joy of Music, he made the point that Beethoven’s melodies were very different than, say, Tchaikovsky’s. Tchaikovsky melodies, such as for example the romantic one in his Romeo and Juliet Overture, are full of dramatic dissonances that pleasantly resolve, big swooping leaps up or down, and crackling rhythms. Looking at Beethoven’s melodies on the page, they are the opposite of what we like about Tchaikovsky’s melodies: Beethoven’s seem downright plain, something like the turned-in homework assignments of a below-average music student. The extreme example Bernstein cites is the melody of the slow movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, which on the page appears to be some uninteresting repeated notes in a basic rhythm of quarters and eighths. The famous opening of the Moonlight Sonata also is rather featureless, again with a lot of repeated notes of the same pitch, and in my last essay I posted, about Bach’s Fifth Brandenburg Concerto, I wrote about the ordinary repeated notes, scales, and arpeggios that populate its opening melody.

Yet we all agree that Bach and Beethoven are great composers, and that Tchaikovsky is decent but undoubtedly a few notches below the immortals. Why is that? I am not sure I can answer that question, but here would like to give you a close look at Beethoven’s Ode to Joy melody and see what we can learn about his genius from how it is put together.

I certainly know what makes a good melody in pop music: simplicity. People want to be able to sing along on the dance floor or in their car as they drive to work and errands. Pop songs have unusually short lines with only a few words in each line, because only musically trained singers have the breathing ability to sing long lines. The pitch range of a pop melody is also generally quite narrow, again to accommodate the untrained music listener who can not sing very high or very low. A few years ago I viewed a bit of the TV show Saturday Night Live for the first time in years and was amazed that the guest featured musician was a vocalist who sang a song which had only five notes in it! I thought to myself, how on earth did that person get chosen to appear on national television? Finally, a pop song’s melody almost always has very simple rhythm. I have noticed a couple of big hit songs of the last few decades have in their melody two half notes as upbeats to a quarter note in the next measure. Put together, it seems the basic rule for writing memorable pop song melodies is simplicity, or, as the acronym KISS has it, Keep It Simple, Stupid.

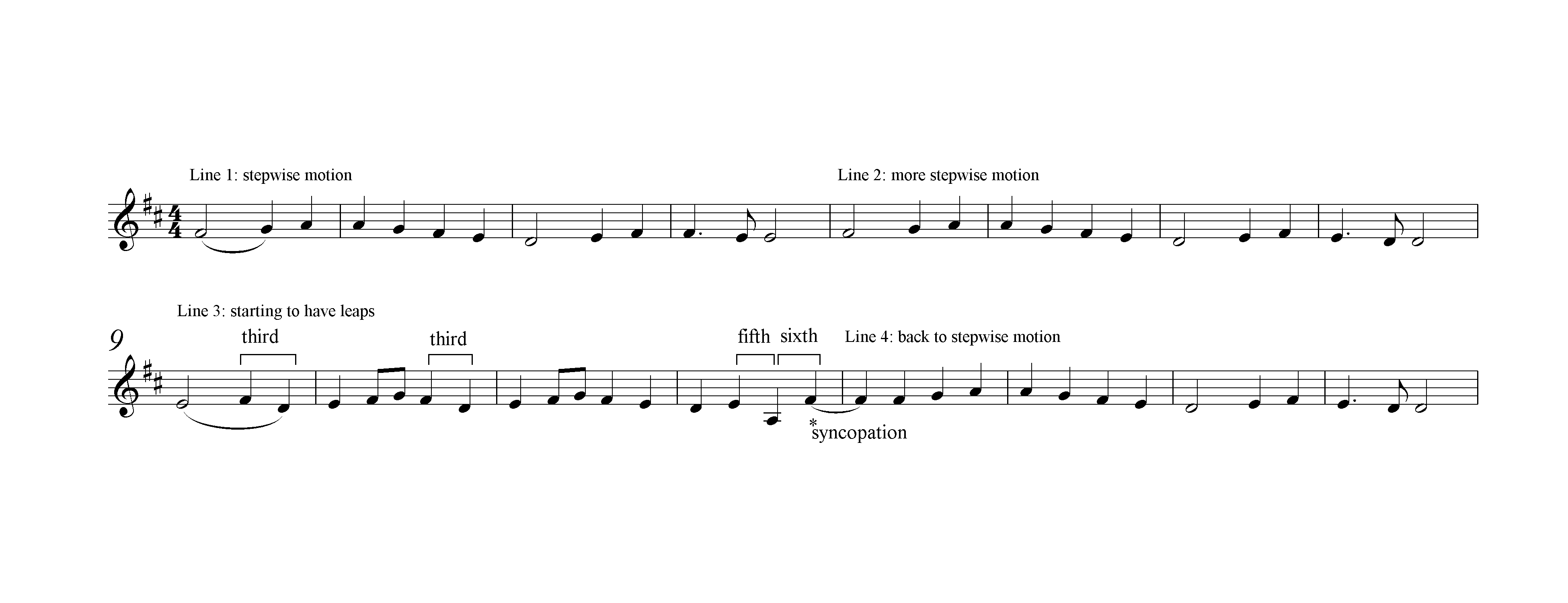

Well, if you look at Beethoven’s Ode to Joy melody, it too has all the hallmarks of simplicity. Or does it? Let’s check it out. The entire melody is pictured below. It has four lines of four measures each, so a total of 16 measures. It is certainly easy to sing or hum. The first, second, and fourth lines are very similar and contain notes in a narrow 5-note pitch range, even narrower than the singer I heard on Saturday Night Live. The melody begins on the third note of the D major scale, an F sharp, goes up to the fifth note of the scale, an A, and down to the first note of the scale, a D. All easily singable. The rhythm is also simple, with plain slow half and quarter notes predominant.

If we look a little closer, we see some other important aspects that also contribute to making this melody easy to remember, understand, and sing. In the first measure, the notes go up. In the second measure, the notes go down. In the third measure, the notes go up, and in the fourth measure, concluding the first line of the melody, the notes go down. In the second line, measures 5-8, we again get the same consistent alternation of measures going up and going down. Again, I can’t help but think that if someone turned this in as a homework assignment for a class at a music school they would receive some critical comments from the teacher that the music was too predictable. But that’s what Beethoven did.

I have certainly known the Ode to Joy for many decades of my life, but it was only last week when I noticed an aspect of this melody I had never noticed before: it is almost entirely composed of stepwise, linear motion. This means that the next note of the melody is nearly 100% of the time a neighboring note, or, in some cases, simply the same note twice in a row. Another way to put it is that Beethoven wrote here lines with no leaps, no gaps between the notes. You can see how this would also help make the melody easier to sing, as naturally it’s less difficult to sing a note that’s close in pitch to the one you just sang, then to have to jump a ways. Even if you cannot read music, you can see visually looking at the graphic below that in all the music in the first 8 measures, Beethoven never moves from one note to the next note in the melody by making a leap: the motion is always to the neighboring next line or space on the staff going up or down, or to the same note twice in a row.

Beethoven’s melody is in what musicians call AABA form, meaning the first, second, and fourth quarters of its total length, the A sections, are extremely similar, while the third quarter, the B section, is an episode presenting something different. This type of form became quite popular through the centuries, because it provides a nice blend of unity and diversity. You certainly get plenty of unity from the many repetitions in the melodic lines: if you compare measures 1-4, 5-8, and 13-16, you will see how similar the A phrases are. But you also get some diversity in the contrasting middle episode of measures 9-12. Overall, the form gives you a feeling of being at home, going away from home in the third line’s interlude, and then returning to home in the final phrase. The popular songs of the so-called Great American Songbook of the early 1900’s, such as Gershwin’s I Got Rhythm, and all the many performances you may have heard of jazz standards which are improvisations based on these old songs, are in this classic AABA form, the same form Beethoven is using here in his Ode to Joy melody.

Probably there were many composers of Beethoven’s generation who could have come up with the basic idea of his melody stated in the first four measures. Where we see Beethoven’s true genius is what he composed for the middle episode of measures 9-12, which I doubt could have been written by any other composer of his time. Up until now, the motion has been perfectly stepwise, but here he starts to finally give you some leaps, some gaps in space between the pitches of the melody. In the graphic, I have put brackets over these moments. In the first measure of this crucial phrase, measure 9 overall, the melody jumps down from F# to D, the distance of a third, the smallest possible leap there is: from an F to an E would be stepwise motion, as would from an E to a D, so from an F directly to a D, skipping over the note E in the middle, is just a small jump. Beethoven immediately reverses direction and after this jump down pushes upward going into the next measure with a scale D-E-F#-G. Near the end of this second measure of the phrase he again drops down by a leap of a third, again opposed in the succeeding third measure of the phrase by the rising D-E-F#-G scale. Finally in the fourth and last measure of this phrase, measure 12, he starts widening the leaps, giving you a fifth leap downward from the E above middle C to the A below middle C, and then an even larger leap of a sixth upwards in immediate response, from that A below middle C up to the F# above middle C. Then, as if nothing had happened, we’re back home: he returns in the fourth and final line of the melody to the simple stepwise motion of its opening. So the experience of the melody as a whole has a definite shape, from the beginning’s constant narrow motions by repeated notes and seconds, to some jumps in the middle of the melody where you get progressively wider leaps of thirds, fifths, and sixths, and finally back to the stepwise motions at the end of the melody, bringing us back full circle.

Taking a closer look at the rhythm of the interlude phrase is also interesting. measures 10 and 11, the second and third measures of the four-measure phrase, are the first occurrences of any beats with two eighth notes. Up until now the melody had been permeated with the broader, slower half and quarter notes, but here these quicker eighth notes help build momentum, driving us to the key 12th measure, the turning point of the melody. At the end of this 12th measure, as we make the big leap up from A to F#, the final note is the one and only syncopation, or unexpected accent, in the entire melody. If he had written the low A as a half note sustaining to the end of the 12th measure, he could have started the 13th measure with an exact repeat of measure 1, with a half note F# and two quarters G and A. Instead, Beethoven brings in the F# one beat early, on beat 4 of measure 12 (marked with an asterisk), and holds that note over the barline so on beat 1 of measure 13, for the first and only time in the melody, you hear no note struck on the initial beat of the measure. This shifting of an attack from the usual strong first beat of a measure to the usually weak last beat of the previous measure creates an accent musicians call a syncopation. These unexpected accents were to become some 100 years later the key element of jazz; however in jazz you hear syncopations constantly whereas here, when Beethoven gives you only one syncopation in 16 measures of music, it really sticks out.

Looking at the big picture, we see how Beethoven built the structure of the melody. He emphasized small stepwise motion for almost the entire melody, creating a smooth, connected feel with basic rhythms of slow, broad notes. Then, in the middle of the melody, a bunch of things all happen at once which support each other: you start hearing faster notes for the first time, you start hearing leaps in the melody for the first time, and these leaps gradually become larger and larger. All these developments work together to drive the music to its first and only syncopation accent at the end of the episode. This moment is a bridge, as the last note of the episode and the first note of the opening melody are the exact same pitch, so Beethoven blends the end of the interlude with the beginning of the familiar opening phrase’s final repetition.

Brahms took a long time to come out with his Symphony no. 1, and when he finally did, critics chided him by mentioning how similar the broad melody of the finale of Brahms’ symphony was to the broad Ode to Joy melody of Beethoven’s symphony. Brahms’ reply was, “any jackass can see that.” Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, composed in the 1820’s, was in conception truly next-level and cast a long shadow on all the romantic composers that lived after Beethoven in the 19th century. As fun as Brahms’ riposte was, after my exploring in more depth Beethoven’s melody recently, I decided the other day to take a listen to Brahms’ melody as well, which I hadn’t done in years. Indeed, I noticed many similarities. It too is 16 measures long divided into 4 phrases of 4 measures each. Its third phrase also drives through repetition to its final measure with a big leap upward to an unexpected accent, followed by a relaxation through the ending fourth phrase. Of course, there are a number of differences so it doesn’t rise to the level of plagiarism, but in form and content Beethoven was clearly the model.

Is Beethoven’s Ode to Joy an example of keeping it simple? I would say no. I would say it is more an example of what they frequently teach young composers, that it can work well to limit your palette, to emphasize particular aspects of music for a particular melody, creating expectations that you can later depart from by writing music that contrasts from the vocabulary you had established earlier in the music. The leap at the climax of Beethoven’s melody at the end of measure 12, from A to F#, is by itself not a big deal, but after Beethoven gives you dozens of narrow stepwise motions in a row, that leap feels canyon-like and huge in context. Beethoven’s building blocks were simple melodic gestures and rhythms, but that was not the end of the story as it is for many pop songs. As the line from the old Louis Armstrong tune I heard in childhood goes, “it tain’t wha cha do, it’s the way chat you do it.” Any composer could have come up with the first four measures of Beethoven’s melody, but only 1 in 1000 could have written the 16 measures as well as Beethoven did here, and of these, only 1 in 1000 could have brought the melody into the grand conception of the entire Ninth Symphony, which became the most influential piece of the 19th century and was played when the Berlin Wall came down and at the Chinese democracy protests in Tiananmen Square in the 1980’s. We all play and compose with the same notes on the piano, it’s how you handle, organize, and shape them into larger forms that make the difference.