home | contact | sound samples | discography | calendar | reviews and testimonials | photos and press materials | site map | mailing list sign-up |

||

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

Essay by Michael Arnowitt, October 2020

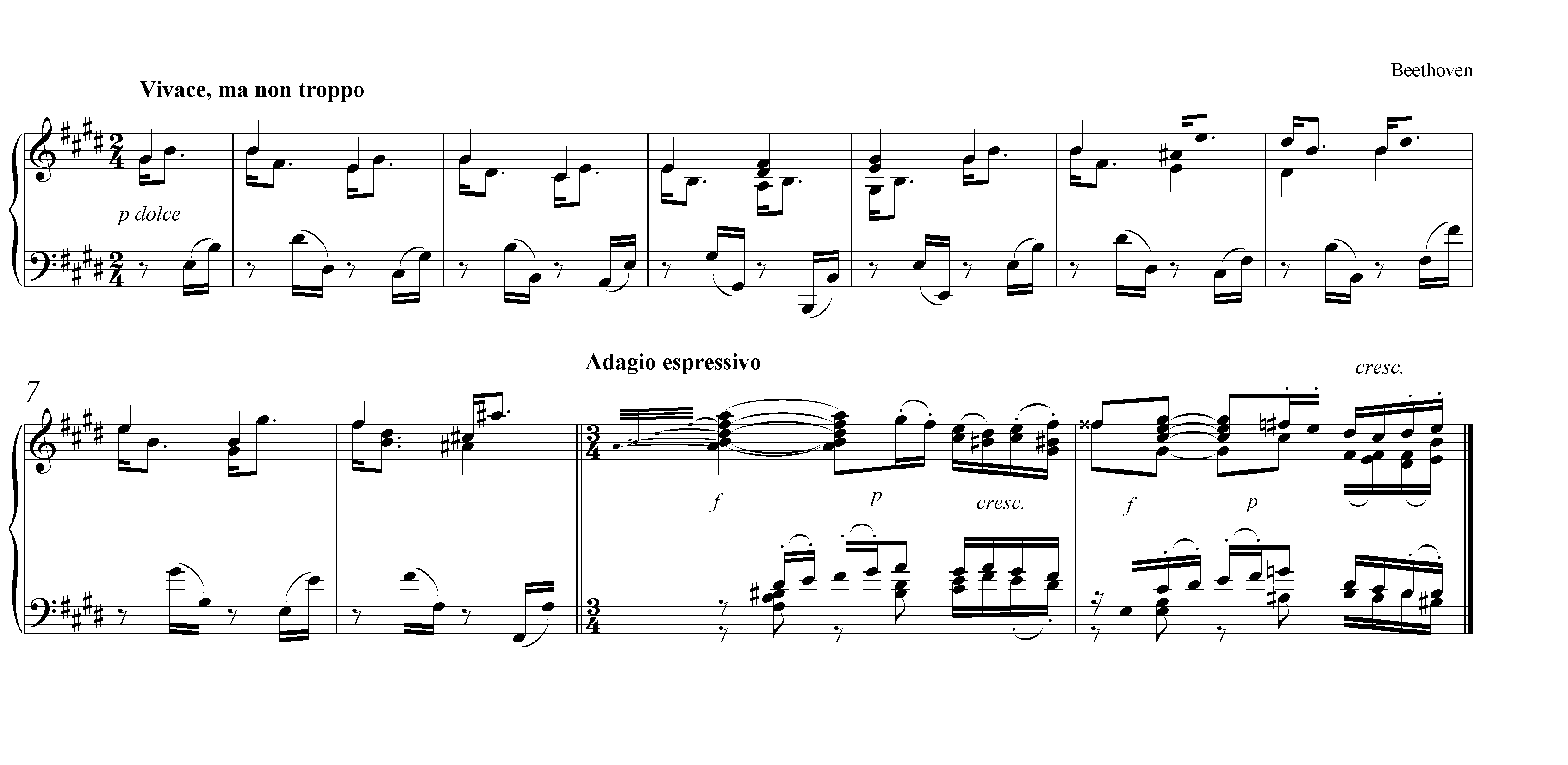

Pictured in the graphic below is the first 10 measures of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata no. 30 opus 109 in E major. The first movement of this sonata is in my top two favorite Beethoven piano sonata movements of all time, along with the finale of his Sonata 32. Itís one of the pieces I chose to play for my father the day before he died in a hospice ward; throughout his entire life, my father had a deep appreciation for Beethoven’s piano sonatas and contributed to my love of music.

I’ve decided to relearn Beethovenís last three piano sonatas and one aspect of the music Beethoven wrote at the end of his life that I find very striking is its increased density, by which I mean that significant events come at you much more rapidly than in Beethovenís earlier music, or that of his immediate predecessors Haydn and Mozart, where the pace of major events is much more relaxed.

They teach you in music school that sonata form has two contrasting themes, and that we sense where we are in the form by the creation of big sections through the dramatic differences of the music of the first theme and the music of the second theme. Typically, the two themes would be a couple of pages apart in the printed music, because the composer writes not just an opening melody but some additional music to go with the first theme in the same character, plus a decent amount of transitional music to bring you gracefully to the second theme.

Beethoven’s earlier Waldstein Sonata is a classic example of this. The first theme has the famous exciting pulsating repeated eighth note chords unusually low in the piano. The second theme by contrast is all thick chords in slower note values high up in the piano in a distant key, and does not enter until the 35th measure, about a full minute after the piece begins.

But near the end of Beethoven’s life, in his piano sonatas and string quartets, he created something very different, a new type of music much more concentrated and intense. In the beginning of his Sonata 30 the second theme surprisingly comes in not some pages later, but just halfway through the second line of the first page. The fleet first theme only lasts 8 measures, a mere 10 seconds of music, dissolving directly into the second theme with no transition whatsoever. In the fragment below you can see the first 10 measures of the sonata, the first theme marked Vivace of only eight measures, and then the first two measures of the second theme under the word Adagio.

It is very tempting as a pianist to broaden the tempo slightly on the eighth measure at the end of the musicís getting louder and higher, but I like playing in tempo without any slowing down straight through to the beginning of the ninth measure so the big strummed chord at the first beat of the slow Adagio second theme is a complete surprise.

On paper, you would think these two themes would be too different from each other to belong in the same piece. The first theme is fairly fast - the second theme is extremely slow. The first theme is comprised of single notes - the second theme has many thick chords. The first theme has a regular flow - the second theme is irregular and has an improvisatory feel. In the first theme each melody note moves by leap to its next note - in the second theme you hear lots of smooth step-wise motion, a note moving to one of its neighboring notes on the piano. The first theme starts in the middle of the piano and descends into the lower area - the second theme often hovers higher up on the piano, above middle C. The first theme is in a time signature of 2 beats per measure - the second theme is in a time signature of 3 beats per measure. The first theme uses simple harmony types such as what you would hear in a typical pop music tune and is in major, while the second theme uses richer, more adventurous and expressive chords and has twinges of minor.

Yet the magic of this music is despite these two themes being so different from each other in every way imaginable, somehow, somehow, they belong together - it all works. On paper, the two themes should clash with each other, but they donít. It reminds me a little of the concept in Taoism of the yin-yang reconciliation of opposites.

To quote Wikipedia, “Yin and yang can be thought of as complementary (rather than opposing) forces that interact to form a dynamic system in which the whole is greater than the assembled parts.” The textbooks have been thrown out. Beethoven is not trying to present a cheap drama of two opposites. The two themes belong together and complete each other, and although I have known this music for over 40 years now, I can’t explain why this is so.