home | contact | sound samples | discography | calendar | reviews and testimonials | photos and press materials | site map | mailing list sign-up |

||

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

Essay by Michael Arnowitt, January 2021

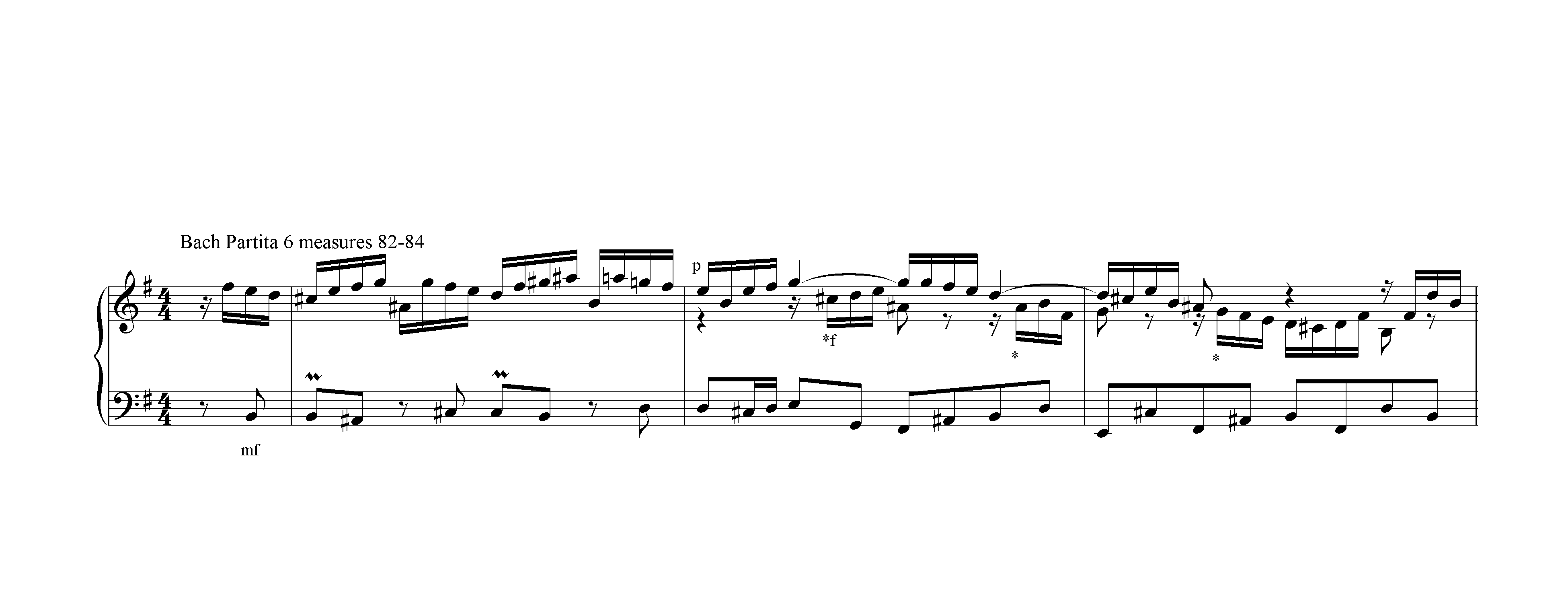

I had a nice moment a couple of days ago practicing at the piano the passage pictured below from the opening Toccata of Bach’s 6th partita in E minor. One of the most basic tools in the pianist’s toolkit is playing different notes and lines of the total texture at different volume levels. In the music world the lingo term for this is dynamics. When I was a young music student I didn’t really understand why they used the term dynamics to mean volume level, but as I got older I realized introducing dynamics to your performances really makes the music come alive. Unfortunately, many musicians perform on autopilot, playing most notes at a medium-loud level, which makes music far more plain-sounding and one-dimensional. I’m probably guilty as well of forgetting to use dynamics in my playing. Yet one of the greatest strengths of the piano as a musical instrument is it is capable of playing extremely softly or extremely loudly and all manners of volume gradations inbetween. This opens up a world of possibilities for how to play music.

When I was young I was told a possible use of dynamics in Bach and other composers of the baroque period is what they called “terraced dynamics,” where you play a certain part of the texture at a differentiated volume level and keep it consistently at that level for a particular passage or section of music. Again, a great idea to which I was only briefly introduced in my music education, but which I really haven’t used as much as I should in my subsequent life as a pianist.

But as I said, I had a happy moment piano practicing the other day when I applied this idea to this piece by Bach. The excerpt shown below is from a section where you are principally hearing three lines of music being played simultaneously. The bass line, played by my left hand in the lower staff, is the main melody. Over the melody in the right hand’s music on the upper staff are two accompanimental voices, one high up (its music has stems going upwards) and one slightly lower, closer to the middle of the piano (its music has stems going downwards). These two accompanimental voices trade, or exchange, four note groups in quick, exciting alternation, with the nuance, because Bach is a great composer, that in the upper part the fourth note of each group is held while the other part answers, while in the middle-level part he brusquely cuts off the last fourth note of each group so its voice has substantial silences, rests between each new phrase.

I tried experimenting with playing these three component parts of the texture at different terraced volume levels and settled on one that I feel really brings the music to life in a vivid way. The lowest part theme I play at mf, medium loud. The highest part I play p, softly. The three short brusque interruptions, their beginning notes marked with asterisks in the image above, I play f, loud. This highlights these three interruptions and turns them into conversational exclamations, first two phrases that are exactly four notes long ta-da-da-da, ta-da-da-da, then a followup and concluding phrase of eight notes, ta-da-da-da-da-da-da-da.

When I was listening the other day to one of my favorite recordings, a disc of Pablo Casals rehearsing an orchestra in Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, he would repeatedly say, “very clear, very clear.” If the three voices of the music in this Bach piece I was working on were played by three different instruments, like a flute for the top line, a violin for the middle line, and a cello for the bass line, it would be fairly easy for the listener to understand the musical ideas because of the different tone colors of the instruments. With a piano playing all three lines by itself, you have to work harder to achieve “very clear” and using different dynamic levels is a great way to, as I said, make the music come alive.

I remember growing up my first piano teacher A. Ramon Rivera gave me as a present one year a book The Joy of Music, a compilation of Leonard Bernstein writings. In the essay on Bach, he offers a nice analogy that listening to certain passages of Bach’s music is like being on a boat in a flowing river and passing islands here and there. I thought of this while practicing this passage, how the two outer voices are the flowing river and the three short phrases with rests inbetween in the middle of the texture are like the islands we pass by in Bernstein’s image.