home | contact | sound samples | discography | calendar | reviews and testimonials | photos and press materials | site map | mailing list sign-up |

||

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

Essay by Michael Arnowitt, March 2021

Here is the seventh in a series of short essays I’ve been writing on music topics in recent months. So far, most of them have been about pieces of piano music I’ve been practicing or have recently performed, but I’ll also be delving into some of my favorite orchestral pieces. Today’s essay is about the beginning of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto no. 5 in D major.

Scales and arpeggios, scales and arpeggios. All beginners who take music lessons are forced to learn how to play scales and arpeggios in every major and minor key. Does working on these very dry-sounding note patterns have any usefulness in the musician’s later life? Absolutely. Composers, from the worst to the greatest of all time, use these building blocks of music in their creations in a diversity of ways. Although I’ve been playing piano for over 50 years now, I still often begin my practice sessions by warming up on these same note sets that have been assigned to beginners around the world for generations.

Bach’s fifth Brandenburg Concerto is in the key of D major. For those of you who don’t know what scales and arpeggios are, a scale is a linear upward or downward motion through the collection of notes of a particular key. An important quality of what makes a scale a scale is that the notes have to be ordered so they follow each other in a stepwise motion, each new note being a neighboring note to the previous note you just played. If I remember my Italian correctly, “La Scala” means “the staircase” and that is a great analogy for what a scale is. You walk a flight of stairs one at a time, and when you’re on a staircase, you naturally move in a straight and consistent direction, either up or down.

The simplicity of the scale idea makes it quickly recognizable to the listener’s ear, a quality great composers have long appreciated. Because a scale, or even part of a scale, really jumps out at us, we are easily able to make connections between different moments of a piece of music. In this way we experience a satisfying sense of unity, a feeling that the music belongs together.

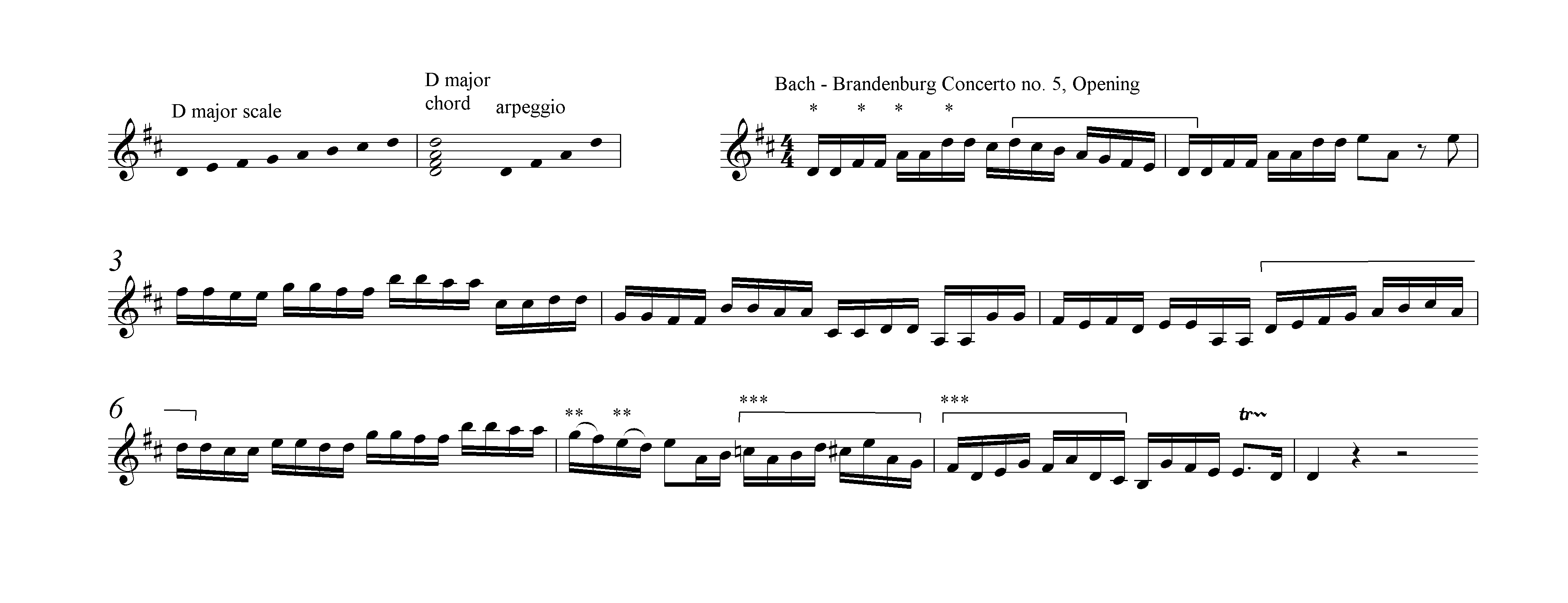

At the left of the top line pictured below are the notes of the D major scale, Bach’s home key for this piece. Each new note is one letter-name higher, so you have a D, then an E, then an F, and so forth up the alphabet of letter-names of the notes used on a piano. By contrast, an arpeggio moves by jumps, not by linear steps. A D major arpeggio takes the notes of a D major chord, shown vertically at the beginning of the second measure in the graphic, and plays them one at a time, again in a single direction either upwards or downwards. Next to the vertical chord you can see the horizontal arpeggio of four notes, a D, an F, an A, and then the high D. One way to think of an arpeggio is to imagine a guitarist plucking through the notes of a chord one by one. Again, frequently there are gaps between the notes in an arpeggio: after the D, you skip the E and go directly to the F, then you skip over the G and go directly to the A, and so forth. So two basic elements of musical motion are exemplified here, proceeding by narrow steps (scale) or wider leaps (arpeggio).

These scales and arpeggios are the foundational building blocks of much of the music we hear, and Bach and Mozart in particular were amazing in how much gas they were able to get out of these seemingly basic and ordinary-sounding materials.

Bach’s concerto begins with an 8-measure long theme in the violins, pictured in the graphic below starting on the right side of the first line. His central idea is to use a lot of repeated notes, that is, little groups of pairs of the same note played quickly twice. These pulsating repetitions create highly energetic music in a particular, distinctive way that is different from other baroque period concertos. I feel sure it is this central feature of these active repeated notes, together with how Bach handles and develops this initial idea, that has led to this piece’s continuing fame and popularity through the centuries.

How does Bach begin the melody? He powers upwards by taking the four notes of the D major arpeggio, marked with asterisks, and doubling each one, so you hear D D, F# F#, A A, and high D D. Then in the second half of the first measure he suddenly reverses course and plunges downwards through a full D major scale, indicated with a bracket, leading you to the beginning of the second measure where he reverses course again an rockets upwards with the arpeggio and repeated notes, ending with the piece’s first rest, a short silence near the end of the second measure.

So far we had a musical event that took up half a measure, the arpeggio of repeated notes going up, then another musical event of a half-measure long, the scale going down, then another half-measure long arpeggio going up. But now he takes the central idea, the repeated note pairs, and really goes to town, suddenly giving you a much, much longer phrase. In the third measure you hear, a little higher on the violin, an F# repeated, then an E repeated, then a G repeated, then an F# repeated, which again is a half-measure’s worth of time, but he blows by that exit ramp and gives you another note repeated, another note repeated, another note repeated, another note repeated, and 8 more notes even beyond that, each of those 8 notes also repeated , filling up the entirety of the third and fourth measures of the melody and creating an amazing sense of momentum like a train at good speed chugging down the tracks. Also, you begin to appreciate, unconsciously, that the notes Bach is doubling no longer need to be chosen strictly from a D major scale or arpeggio, but rather the idea is now so much in our heads that any note can be repeated and we sense it as being related to the opening of the piece. So, in these third and fourth measures Bach careens wildly up to a high B and skids way down to the violinís lowest A, zigzaggin joyously all the way.

On the fifth measure he brings back the D major scale (marked again with a bracket), but with a couple of twists: one, it’s rising now instead of falling as we heard it in the first measure, and two, it is joined by the cellos in perfect harmony thirds , so the scale’s eight notes are reinforced and made stronger and more vigorous. In the sixth measure, the train returns for another whole measure of repeated note pairs.

One sees here how Bach avoids the potential monotony the repeated note idea could have produced in the hands of a lesser composer. Clearly, if Bach had just doubled every note for the entire length of the melody’s eight measures, the music would have become stiff and predictable. Instead, he gives life to the music through constantly varying the length and nature of the musical events, so to again summarize our travels so far, we heard half a measure of repeated notes of an arpeggio, half a measure of a scale, back to a half a measure of the opening repeated notes, then a little quick silence and break in the line, then two full measures of a long line of repeated notes, then a quick scale again but one supported by the bass line in parallel motion, then back to the repeated notes, but here neither the super-short half measure version nor the super-long two measures version, but now a phrase thatís one measure long, so medium in length. It is all these little decisions of proportions, sequencing, how the melody interacts with the bass line, and other details that elevate this music from a random composer having a catchy idea to a memorable work of art.

In the last two measures of the melody he relaxes and gives you more variety, moving away from the simple building blocks of scales, arpeggios, and repeated notes he populated the line with up to this point. In the first six measures, all the notes were separately articulated, the violin bow moving alternately down and up, down and up throughout. But here, finally, at the end of the melody, he gives you for the first time a couple of slurs, where two notes are played in a row on the same bowstroke, which briefly creates a more graceful, smoothly connected sound (Iíve marked these two slurs with double asterisks). Then, in the second half of this next to last bar, he concocts a brand-new curlicue shape of eight notes (marked with three asterisks) and repeats this more rounded shape a little lower at the beginning of the final measure of the theme, while the bass line chips in with some jovial repeated notes of its own in accompaniment. These active cello notes seem to me to be conversational, as if to say, “I hear what you’ve been saying all along, and we’re on the same page.” The melody wraps up with a short trill. Perfect.

Many minutes later in the concerto Bach does something musically that really brings a smile to my face: he takes the first half-measure of the piece, the four pairs of repeated notes going up the arpeggio, and turns this gesture from melody into accompaniment, bringing these notes back quietly in the orchestra here and there as little light interjections, creating interplay with the three soloists of the concerto, the flute, violin, and keyboard. The switching of roles and the blurring of lines of what is melody and what is accompaniment is another topic that’s been interesting me lately, a subject I plan to explore in some future essays.

I play many different Bach pieces from time to time around the house which go without comment from my wife, but as I was thinking about this essay and was playing through the music of the opening theme on the piano, she perked right up and asked me what piece this was. I sometimes wonder if pieces I think of as great truly are great, or do we like them so much because we are biased by their familiarity. But here was proof that this sturdy and lively music is inherently innovative, that within seconds, on a first hearing it immediately caught her ear. Bach took these basic building blocks - scales, arpeggios, and repeated notes - and with his imagination created something unique, spirited, and vigorous that still affects us as fresh-sounding 300 years after he put pen to paper.